Effects Of U.S.A Sanctions on Iranian Military Spending

CAN IRAN AVOID SANCTIONS AND BUILD ITS PROXY WAR

Editor Note: This article was written in 2022 and remains unchanged; events and developments after this date are not reflected.*

Abstract

Sanctions are used as the most common policy tool by international actors to respond to the internationally unlawful acts of the target country. The United States leads the list when it comes to sanctioning its rivals and making decisions on targets. The United States, which imposes sanctions on the private sector, banks, the military, and any natural or legal person, is the country that imposes the greatest number of sanctions against Iran. For example, it is imposing more sanctions against Iran than North Korea, Venezuela, Cuba, and Libya combined. The article focuses on the impact of the military and economic sanctions imposed on Iran by the United States of America on military expenditures.

Introduction

In 1979, when the regime of the country changed along with the government, Iran's security approach shifted to a different axis. The new regime put volunteer militias into service for maintaining order and for problems that may arise inside Iran. With the expulsion of the country's former leader Shah, the relations between Iran and the United States entered into different crises. The hostage of the American consulate staff, and Iran's support of non-state factors in other countries of the Middle East, especially in Lebanon, brought the tensions between the two countries to the highest level. Reagan's definition of Iran as a state sponsor of terrorism during the Iran-Iraq war is important in terms of showing the American perspective on the new regime and reconsidering its policy tools[1]. In addition, it should be remembered that the first sanctions were imposed at an earlier date, as a reaction to the raiding of the US Embassy in 1979[2]. In 1985, sanctions were introduced to restrict the sale of arms to Iran, and all states except China supported and implemented this decision. By the year 95, the Iranian regime saw the Iraq war as an opportunity and suppressed the rights and demands of those who rival the state administration or the minorities, with militia forces and revolutionary guards inside[3]. Since 1979, the Iranian Republic has supported proxies in the Middle East and made these groups work directly and indirectly for the Iranian national interests[4]. Today, there are various armed proxies and political parties supported by Iran militarily and politically in the Caucasus, Levant, Middle East, North Africa, Arabian Gulf. These groups, on the one hand, consist of partially legitimate organizations such as Lebanese Hezbollah, which are located within the system of the country in which they were established militarily, and are also recognized by some international actors, on the other hand, they can be listed in a wide range from brigades accused of foreign soldiers and war criminals used in the Syrian Civil War. While it is debatable whether Iran uses proxies for the strategic defense of the state or to export terror to other states, these groups certainly support the country's struggle to become a regional power[5]. In addition, the violent transformation of the protests after the Arab Spring and the seizure of a large amount of land by Isis in Syria and Iraq also accelerated Iran's foreign intervention in both of the above countries[6]. Nearly 100,000 armed Hasdi Sabi militias gathered in Iraq at the call of the Shiite leaders, and the brigades in which immigrants from Afghanistan and Pakistan were trained and recruited in Syria were used effectively for the interests of Iran in the war. Iran's actions towards its regional interests and the groups it supports have caused the United States of America to directly impose sanctions on these powers since 1995[7]. The purpose of America's sanctions on Iran is to prevent Iran from possessing nuclear weapons and to put the country in a position that will not harm the Middle East peace policy. For this reason, America imposes sanctions including on the Iranian army and its members or any group directly affiliated with them. Between 1995 and 2020, five administrations – Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trump, and Biden – sanctioned 11 Iranian proxy groups in five countries[8]. They also sanctioned 89 leaders from 13 groups supported by Tehran. The last and most comprehensive of these sanctions was made by the American Prime Minister Trump, who carried out full pressure policies on Iran. He further criticized this deal and the lifting of sanctions by declaring that ‘[I]n the years since the deal was reached, Iran’s military budget has grown by almost 40 percent – while its economy is doing very badly. After the sanctions were lifted, the dictatorship used its new funds to build its nuclear-capable missiles, support terrorism, and cause havoc throughout the Middle East and beyond[9].

The article consists of 4 parts: presentation of the hypotheses, summary of the literature, presentation of the findings, and conclusion. In the first part, the relationship between military expenditures and economic and military target sanctions is discussed and a brief perspective on the causality relationship between the hypotheses is presented. The second part includes the definition of the relationship between military expenditures and economic growth and a short briefing on the literature reviews in which sanctions and this relationship network are analyzed. The third chapter includes a discussion of the links between the hypotheses and findings from the IMF, the World Bank and published articles. The fourth section is the conclusion section regarding the results of the studies.

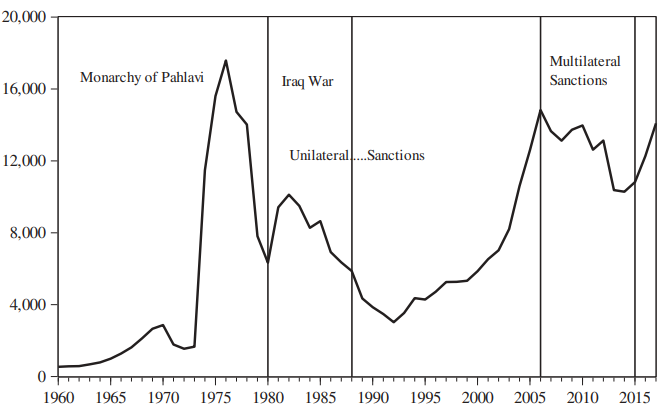

Source: SIRPI [10]

Hypothesis 1: Unilateral USA sanctions have a positive effect in terms of increasing Iranian military spending.

Hypothesis 2: Income-targeted sanctions have a negative impact on Iran's military spending.

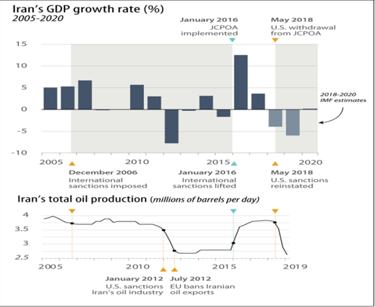

The graph above shows military spending in monetary terms from 1995, the year of the first military sanctions, to the date after the nuclear agreement with Iran.

Military spending under multilateral sanctions from 2006–2015 consistently decreases while a similarly consistent trend is not observed during the period of unilateral sanctions (1979–2005). Following the Iran Nuclear Deal and lifting of multilateral sanctions, can be observe that, an increasing trend in the real military spending of Iran[11] (2015–2017). There is another situation that needs to be taken into account regarding the sanctions. These are the number of states that impose and are involved in the sanctions. When the sanctions are examined historically, it is seen that the one-sided ones are more numerous. Despite this, there are also cases where many countries are involved. For instance, the sanctions that were approved by the UN after Iraq's invasion of Kuwait and that were imposed after Iran's enrichment of nuclear uranium[12]. It is generally argued that multilateral sanctions, due to the cooperative and coercive behavior of participating nations, are more likely to succeed compared to the unilateral variety (Caruso 2003; Dizaji 2018b) In this case, multilateral sanctions reduce Iran’s military spending about 77% in the long-run.

Relations Between Hypotheses

The article focuses on two effects of sanctions. These are security and income. The security effect includes a possible future military intervention message given by the targeting country to the targeted country, in our case it is Iran. For this reason, countries tend to increase their security and military expenditures. Regarding the income effect, will restrict the financial resources of the target country and contract its budget on defense and other functions[13].

It is expected that the size of the sanctions applied within the scope of the military will be large enough and that the sanctions that will not have a destructive effect on the country's economy in the field of finance and income will allow the target country to increase its military expenditures. At the same time, it is expected that the sanctions that will significantly narrow the income and financial infrastructure of the targeted country and restrict its access to international funds will reduce the financial budget, whereat military expenditures.

Literature Review

Understanding the determinants of military spending has been an important topic in literature due to significant positive and negative impacts of military on economic growth[14].

Is there a relationship between military spending and economic growth?

The literature is divided into two on this issue. According to the first group of academics, higher military spending positively affects economic growth (see meta-analysis of Alptekin and Levine, 2012 which finds positive effects of military expenditure on economic growth for developed countries and insignificant effects for developing countries). In a case study of Iran, Farzanegan (2014a) uses the annual data from 1959 to 2007 and simulates the response of Iran’s economic growth rates to positive shocks in its military spending[15]. He concludes that any significant fall in Iranian military projects may also reduce the speed of economic growth in Iran due to major forward and backward linkages of the military complex with other sectors in the Iranian economy.

The other group of academics explains that Military spending has a negative effect on economic growth. (see d’Agostino et al., 2017 for robust evidence on long run negative effects of military spending.

They suggest that the larger size of military spending has high opportunity costs as it reduces the financial capacity of the state to invest in public goods such as education and health.

Increasing budget deficits and external debts are other reasons for the negative effects of military spending on growth (Dunne et al., 2004).The reviews in the literature against military expenditures and economic growth are like this in briefly.

In order to understand the economic growth relationship of military expenditures, it is necessary to focus on the factors that affect the expenditures. In this situation, two main types of approach are employed to explain different levels of military spending. These are theoretical and empirical. Theoretical approaches can be listed as arms race model, socio-economic, political and strategic factors, population size, national income, international trade, foreign aid, political institutions. Empirical approaches are case studies in which data analyzes from South Africa, Turkey, and Egypt are made. A brief literature review of theoretical and empirical explanations is given below.

Arm Race Model:

The arms race model primarily focuses on the military spending of potential enemies and/or allies to explain the military budget of a country (Richardson 1960). The initial version of this model was based on the bilateral relationships but proved to be less successful in explaining the changes in military spending of countries (Majeski and Jones 1981)

Socio-economic, political and strategic factors: This model utilizes socio-economic, political and strategic factors to explain different sizes of military spending (Dunne and Perlo-Freeman 2003; Dunne, Perlo-Freeman, and Smith 2008; Yildirim and Sezgin 2005;

Population size: Studies such as Dunne and Perlo-Freeman (2003), Dunne, Perlo-Freeman, and Smith (2008) and Collier and Hoeffler (2007) show a negative effect of population size on military spending.

National Income: When using GNP as a measure of national income, Dunne, Perlo-Freeman, and Smith (2008) found it to have a significant and negative effect on military expenditure. Dispute them, Collier and Hoeffler (2007) use GDP per capita as their measure and found it to have a significant and positive effect.

International Trade: According to Polachek (1992) and Russett and O'Neal (2001), Polachek (1980) trade promotes peace because conflict hurts trade.

Foreign Aid: Collier and Hoeffler (2007) also investigate the effect of foreign aid on military spending. While the effect of aid is conditional to the quality of institutions in the recipient economy (Kono and Montinola 2013), nonetheless, they show that the direct effect of aid on military spending is significant and, on average, 11.4% of development aid leaks into defense budgets.

Political Institution: Smith 2008; Nordhaus, Oneal, and Russett 2012). Dizaji, Farzanegan, and Naghavi (2016) show the relevance of political institutions in the allocation of government spending between military and non-military purposes.

Why does it matter to find the correlation between Military spending and economic growth?Sanctions are the most common tools of choice before military intervention for the target country. It is applied in various ways by the sending country in order to punish the military actions of the target country or the practices against international law. Starting from the Iranian example, some conclusions can be drawn. The US sanctions to restrict Iran's military expenditures basically have three purposes. These, respectively, are to prevent the Army from owning nuclear weapons, to prevent the supply of weapons to Iran's proxies in the Near East and Asia-Afghanistan, and to ensure the security of their Allies in defense agreements. Therefore, every step of Iran that will cause political instability will be seen by America as a move against its allies and will be faced with obstruction. As a result, the relationship between military expenditures and economic growth will provide a base and reference to American lawmakers to determine the mainstay and target points of the sanctions against Iran. Iran has a number of differences from modern states in terms of the organization of the army. In addition to being an army affiliated to the religious leader, called IRGC (artesh), it is also an actor that has its own companies and plays an important role in the Iranian economy. When it is not guarding the revolution, it is a business[16]. After the end of Iran's war with Iraq in 1988, the IRGC began its presence in the Iranian economy. It has since become one of the most powerful national players, controlling perhaps one-third of the Iranian economy[17]. The IRGC and its affiliated firms try to expand their market share, especially in the oil and gas industry. The IRGC has also established its own banks such as Ansar Bank and Mehr Finance and Credit Institution[18]. Lastly, the IRGC is rapidly expanding its influence on different aspects of the formal and informal Iranian economy[19]. Able to fund its military expenditures, the IRGC plays an active role in economic growth and job creation by investing in oil companies and other industries in Iran. Therefore, there is a point where the sanctions imposed by the United States to prevent Iran's military expenditures and to ensure regional stability are stuck. Although the sanctions target military expenditures, arms sales and transfers, Iran's military structure is intertwined with financial markets. In addition, it is possible to set aside the income from the fields they control in oil production for military expenditures. For this reason, sanctions aimed at reducing Iran's incomes by targeting economic, financial infrastructure and trade, and thus affecting its military expenditures, are closer to success.

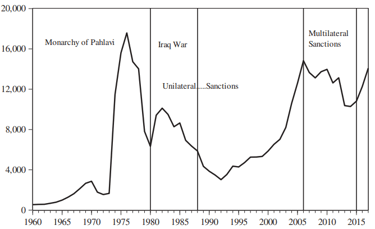

SOURCE: IMF 2019[20]

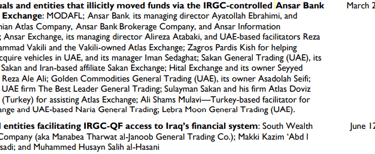

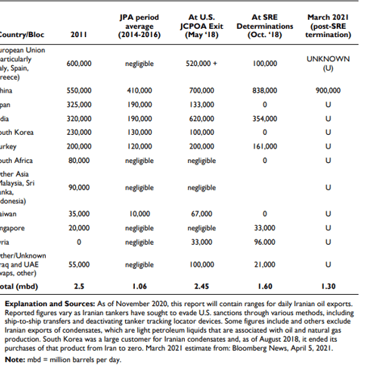

A large part of Iran's foreign trade and income consists of oil exports and petroleum-oriented industrial products. Therefore, it is necessary to learn whether international and unilateral Sanctions have a positive or negative effect on Iran's economic growth - along with the increase in government spending. As can be seen from the table, Iran's oil production is in a controlled manner, starting from 2006 until the US sanctions in January 2012 and the European Union's prohibition of oil exports from Iran in July of the same year. It should be added here as a note that China, to which Iran is assisted in breaking sanctions and exporting oil, has also significantly reduced oil production. From the implementation of the JCPOA in January 2016 to May 2018, during the period when the USA withdrew from the JCPO and imposed the sanctions again, economic growth is seen with oil exports. Hence, it can be said that the sanctions on oil hinder Iran's economic growth.

Oil imports from Iran by countries/Bloc’s

To prevent Military Expenditures through finance and financial sanctions?

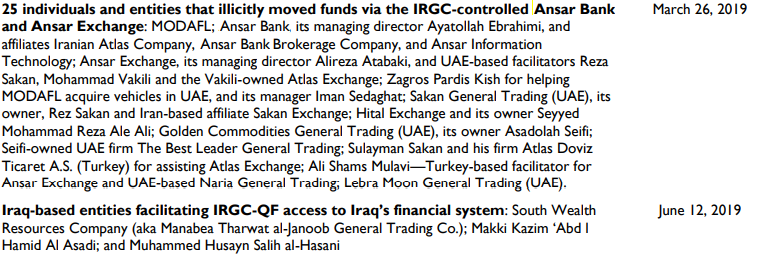

Source: CRS Report R43311, Iran: U.S. Economic Sanctions and the Authority to Lift Restrictions, by Dianne E. Rennack.

In the table, we see the sanction decisions against Ansar Bank, which is owned by Iran's military ranks. The decision covers not only the bank, but also its collaborators in Turkey and Iraq, where the bank carries out financial transactions. Although it is not certain how the sanction decision has affected the military expenditures in the last two years, it is important in terms of showing how strong the Iranian army is in accessing financial markets. We can see the failure of the sanctions that do not target finance and Iran's income in Trump's speeches. As we quoted in the first part, he expressed the positive effect of the sanctions on Iran in the economic field on Military expenditures with the following words. ‘[I]n the years since the deal was reached, Iran’s military budget has grown by almost 40 percent – while its economy is doing very badly. After the sanctions were lifted, the dictatorship used its new funds to build its nuclear-capable missiles, support terrorism, and cause havoc throughout the Middle East and beyond. The nuclear deal has contributed in two ways to Iran's increase in military spending, although Iran's sanctions on military and proxy forces have remained constant. The first of these is that companies affiliated to the Revolutionary Guards export oil, including the companies mentioned in the resolution draft above, and fund the army and proxies with the revenues obtained. On the other hand, the government's ability to finance the army with the increasing incomes related to trade and oil exports.

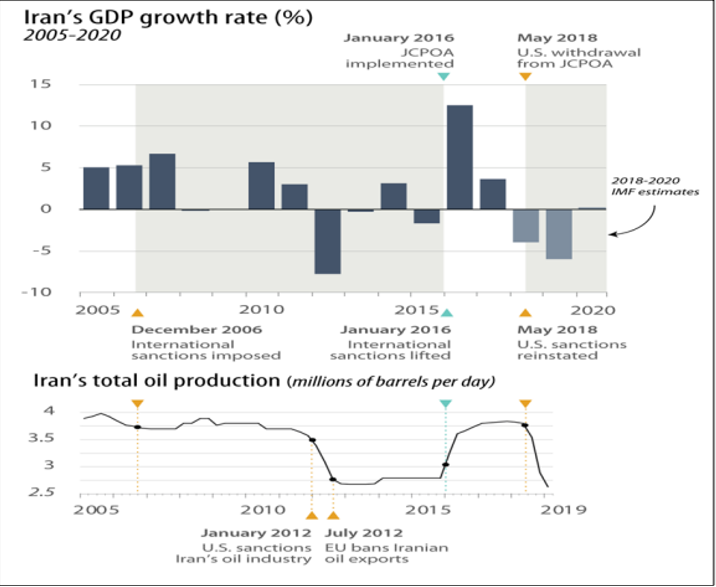

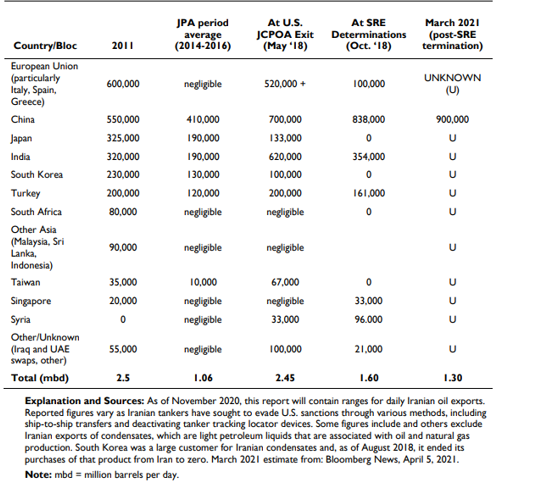

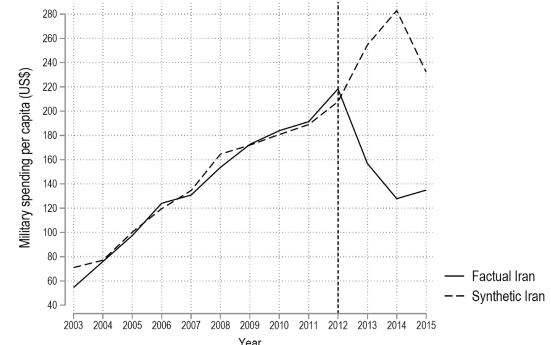

Trends in military spending per capita, (US$): Iran versus Synthetic Iran.

Source, calculated by Mohammad Reza Farzanegan

Figure shows the per capita military spending trajectory of Iran and its synthetic counterpart for the 2003–2015 period.

The synthetic Iran almost exactly reproduces the per capita military spending for Iran during the entire pre-international sanctions period but the two lines diverge from each other significantly starting in 2012. While per capita military spending decelerates in the factual Iran, per capita military spending in the synthetic Iran keeps ascending at a pace similar to the pre-2012 sanctions period. The difference between the two series continues to grow towards the end of the sample period. Therefore, the results imply a significant negative effect of the international sanctions on Iran’s military spending[21]. When Mohammedi's analysis and data sets are combined, it is confirmed that our second hypothesis, the sanctions targeting the economy, oil exports, trade, financial markets, reduce Iran's military spending.

Conclusion

Iran entered a form of government in 1979 where the regime took an Islamic turn. In the protests for the exile of Shah and the establishment of the new regime, the American embassy was raided. In the following years, direct and indirect attacks from Iran on American targets in the Middle East increased. In the light of the above reasons, the United States of America has been applying sanctions under various titles against Iran since 1979. Sanctions are divided into two in terms of scope and target: military sanctions to prevent the army and affiliated proxy forces, and, economic and income-based sanctions that targeting for the country to comply with international law norms. In the study, data collected from the World Bank and IMF, and data and data sets in the literature were used. the findings are stated. Iran's military spending tends to increase when US sanctions against Iran's military and proxy powers remain stable and economic sanctions are put in place. The sanctions, which cover economic, oil, trade, finance and restrict Iran's access to international markets, tend to reduce Iran's military expenditures.

References

Alptekin, A., Levine, P., 2012. Military expenditure and economic growth: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 28, 636-650.

Caruso, R., 2003. The impact of international economic sanctions on trade: an empirical analysis. Peace Economics, Peace Science and Public Policy 9(2),

d’Agostino, G., J. P. Dunne, and L. Pieroni. 2017. “Does Military Spending Matter for Long-Run Growth?” Defence and Peace Economics 28 (4): 429–436. doi:10.1080/10242694.2017.1324723.

Dizaji, Sajjad Faraji; Farzanegan, Mohammad Reza (2018) : Do sanctions reduce the military spending in Iran?, MAGKS Joint Discussion Paper Series in Economics, No. 31-2018, Philipps-University Marburg, School of Business and Economics, Marburg

Dizaji SF (2014) The effects of oil shocks on government expenditures and government revenues nexus (with an application to Iran’s sanctions). Econ Model 40:299–313

Dizaji SF (2016) Oil rents, political institutions, and income inequality in Iran. In: Alaedini P, FarzaneganMR (eds) Economic welfare and income inequality in Iran: developments since the revolution. Springer, Berlin, pp 85–109

Dizaji SF, Bergeijk PAG (2013) Potential early phase success and ultimate failure of economic sanctions: a VAR approach with an application to Iran. J Peace Res 50(6):721–736

Dizaji SF, Farzanegan MR, Naghavi A (2016) Political institutions and government spending behavior: theory and evidence from Iran. Int Tax Public Finance 23:522–549

Dizaji, S. F. 2018a. “Trade Openness, Political Institutions, and Military Spending (Evidence from Lifting Iran’s Sanctions).” Empirical Economics. doi:10.1007/s00181-018-1528-2.

Expanding business empire of Iran's Revolutionary Guards, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-10743580 (accessed 1 February 2022).

Farzanegan MR (2011) Oil revenue shocks and government spending behavior in Iran. Energy Econ 33:1055–1069

Farzanegan MR, Markwardt G (2009) The effects of oil price shocks on the Iranian economy. Energy Econ 31:134–151

Farzanegan, M. R., M. M. Khabbazan, and H. Sadeghi. 2016. “Effects of Oil Sanctions on Iran’s Economy and Household Welfare: New Evidence from a CGE Model.” In Economic Welfare and Income Inequality in Iran: Developments since the Revolution, edited by M. R. Farzanegan and P. Alaedini, 185–211, New York: Palgrave Macmillan/Springer Nature

Sajjad F. Dizaji & Mohammad R. Farzanegan (2021) Do Sanctions Constrain Military Spending of Iran?, Defence and Peace Economics, 32:2, 125-150, DOI: 10.1080/10242694.2019.1622059

SIPRI. 2018. SIPRI Military Expenditure Database. Solna: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Smith, R. 1980. “The Demand for Military Expenditure.” Economic Journal 90 (363): 811–820. doi:10.2307/2231744.

Smith, R. 1989. “Models of Military Expenditure.” Journal of Applied Econometrics 4 (4): 345–359. doi:10.1002/ jae.3950040404.

World Bank. 2018. World Development Indicators. Washington, DC: The World Bank Group.

Iran's military spending tends to increase when US sanctions against Iran's military and proxy powers remain stable and economic sanctions are put in place. The sanctions, which cover economic, oil, trade, finance and restrict Iran's access to international markets, tend to reduce Iran's military expenditures.

Effects Of U.S.A Sanctions on Iranian Military Spending

Can Iran Win the Proxy War?